👋 Hi there! Please go to Canvas for our official fall23 course website.

This here is a draft site currently under construction 🚧. (Bug reports very welcome though; thanks!)

Table of contents

Overview

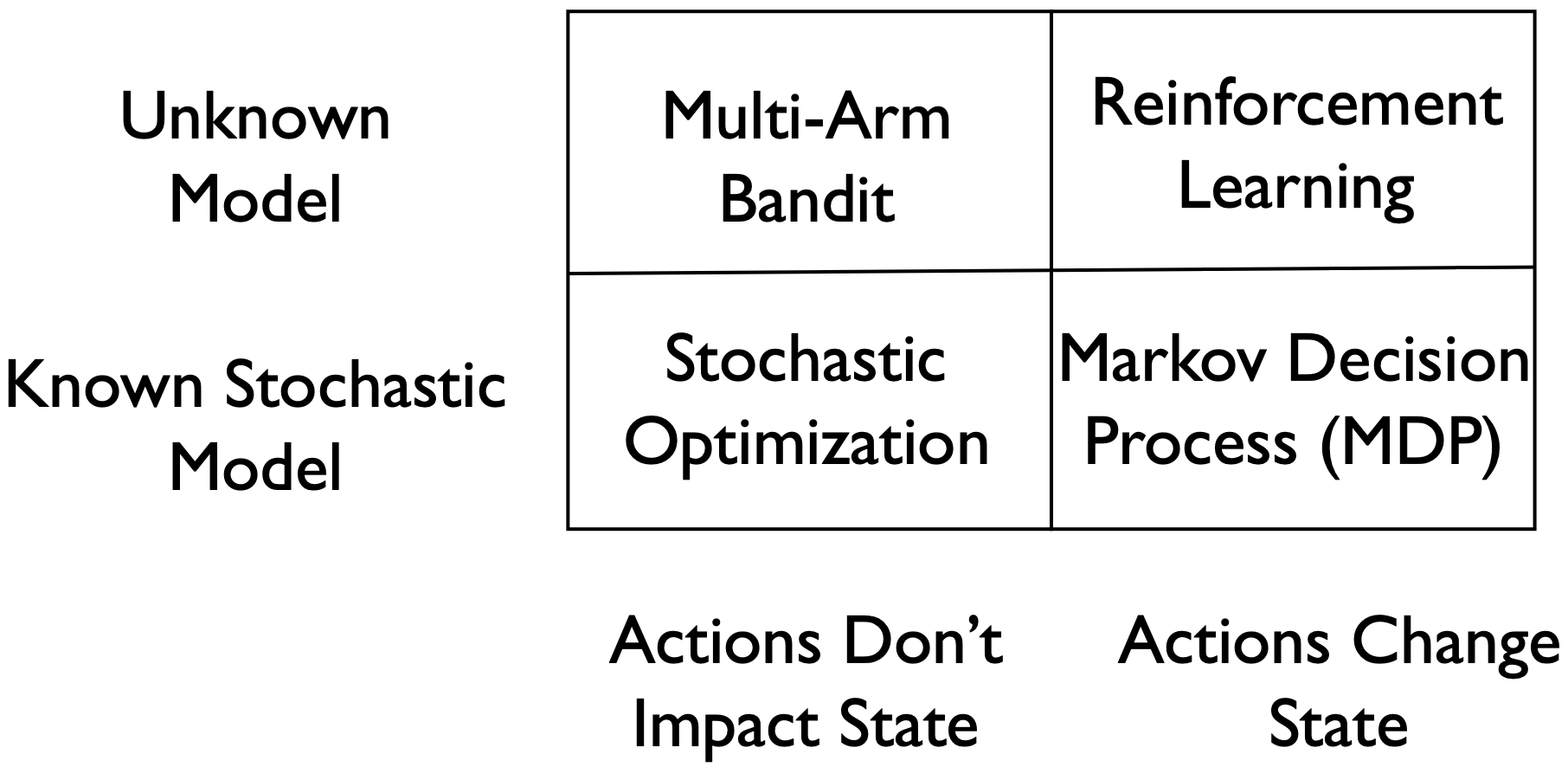

We will start with example and applications of this field and give a general framework for decision making models under uncertainty. Then we will discuss 4 different scenarios – with different state dynamics and known or unknown models.

Later, we will focus on 2 scenarios of these 4, the stochastic optimization, which assumes fixed state and known model, and multi-arm bandit, which assumes fixed state but unknown model. The other scenarios will be covered in coming lectures.

Sequential Decision-making Problems (Under Uncertainty)

Decion-making versus Supervised Learning

For easier understanding of our problem, we first make a comparison between decision making and supervised learning. In supervised learning, we work with a set of features and a target and learn a function mapping from the features to the target. The decision making problem actually builds upon that. In this setting, we not only want the prediction of the target to be correct, but want to learn about the environment as well, so that we can make decisions and interact with the environment.

As shown in the diagram in Figure \ref{diagram}, we do learn a model about uncertainty and that helps us to decide what to do, upon that, we can make a decision, interact with the environment and observe new data, and continue the iteration again. Eventually, we will end up with a sequence of decisions.

Sub-categories of Decision Making

- The four big types of sequential decision-making problems

- Bandits

- MDP

- RL

- Stochastic optimization

and their connections and differences. The “under uncertainty” modifier is really what makes these problems interesting and practical.

and their connections and differences. The “under uncertainty” modifier is really what makes these problems interesting and practical.

Stochastic optimization

(Known model, fixed state)

Suppose we are a retail store manager and we need to decide what to put on the shelf for an entire winter season. Let’s assume people’s demands and preferences are approximately unchanged every year, so that the model is known if we look at the historic data. Also, people’s demand is not affected by what we put on the shelf, so there’s no impact of the actions on the state. What we want is to decide what to stock in the market and the reward is how much money we make. As a summary,

- State: customer demand

- Action: how much inventory to stock subject to various constraints

- Transition Kernel: no transition

- Reward: revenue

This scenario is called stochastic optimization.

Bandits

(Unknown model, fixed state)

Suppose we are designing an online e-portal where we need to decide what contents should be shown to a new customer on the website. Depending on the customer’s preference and what we show to him, the customer may or may not continue to engage with our website and we want the customer to engage. We can assume all the customers are from some unknown population, which is the state of the decision making problem. The population will not be affected by the actions we take, thus there’s no transition between states. The reward is positive if people continue to engage, and negative vice versa.

As a summary,

- State: customer population

- Action: which of the N pages to show to the arriving customer

- Transition Kernel: no transition

- Reward: conversion if right page, loss of opportunity if wrong page

This scenario is called multi-arm bandit.

MDP

(Known model, dynamical state)

Let’s suppose we are designing an automatic chess player, but only to beat a specific player. This player is well known by us and can predict what he will do in any situations, which corresponds to the known transition kernel in our decision making problem. The board position, which is the state, constantly changes, and the actions is to decide is to play a move of the chess given a state. The reward will be positive if we win and negative if we loss.

As a summary,

- State: board position

- Action: which of the feasible moves to play

- Transition Kernel: change in board position due to play of opponent, which is \textbf{known}

- Reward: win ($+l$) or loss ($-l$)

This scenario is called Markov Decision Process, or MDP.

RL

(Unknown model, dynamical state)

Suppose we are doing the same thing as the previous chess playing scenario and the only different thing is that we are now playing with a completely unknown player. Everything is as before, except that we do not know the transition kernel, i.e., we don’t know what the player is going to do given the board position, and thus we need to learn as we play.

As a summary,

- State: board position

- Action: which of the feasible moves to play

- Transition Kernel: change in board position due to play of opponent, which is \textbf{unknown}

- Reward: win ($+l$) or loss ($-l$)

This scenario is known as reinforcement learning.

Different fields that study these problems:

- Control theory (especially robust control)

- Operations research

- Finance

- Social sciences

Some comments on each field’s unique challenges. On one hand, good that a single framework has so many applications; on the other hand though, inevitable notational mess.

MDP

- $S$: a state space which contains all possible states of the system

- $A$: an action space which contains all possible actions an agent can take

- $P(s’|s,a)$ a stochastic transition kernel which gives the probability of transition from state $s$ to $s’$ if action $a$ is taken. This transition can be deterministic as well. Implies by this notation is that $s$ is the current state; $s’$ is the next state, or the state we ended in.

- $R: S \times A \to \mathbb{R}$: a reward function that takes in the state and the action and gives back a real value reward.

- $\gamma \in [0,1]$: a discount factor that re-weight long term and short term rewards

Sometimes also horizon.

Math is cleaner in infinite-horizon case. Why? well, because when things have been run for a long long time, things would have “settled down” or “converged” and the past history – at whatever timestamp you slice it – no longer matter. In the literature, sometimes finite-horizon problems are also called episodic; whereas infinite-horizon ones are called continuing task.

As an aside, this is a general pattern. Asymptotic regime allows you to “cancel” out a lot of things, take limits, etc. (But not very practical; this intrinsic tension motivates lots of research in engineering)

A couple of more comments:

- States versus observation.

- Rewards are what we immediately see but not our final goal. We’re in the game for the long run, so it’s the sum of rewards that we go after. These are the so-called value functions, which we’ll define more precisely and need to comment with more details. For now, remember this intuitive punchline: rewards are short-term thing, values are long-term thing. We want to do good in the long run.

- Fundamental to the long-term versus short-term performance is the tension between exploitation and exploration. Exploitation does well in the short-run; exploration may help us do well in the long-run (even if potentially losing out somewhat in the short-term).

- Sometimes in the literature, the rewards model would be a mapping of (s, s’, a) to (r). In other words, the reward you get not only depends on your current state, and your current action, but also the state you ends in (based on the generally stochastic transition). One such example would be, when you buy a lottery at a particular store, the (monetary) return/reward you get depends on if you actually win. Note, however, that such reward model distinction really do not matter at all in the infinite-horizon case – again, coz convergence cancels that out. Even in the finite-horizon case, all the math works the same by thinking of the future-dependent reward as future-independent, but the horizon got shortened by 1.

- In the infinite-horizon set up, the discount factor has to be strictly less than 1, for making sure the infinite-length rewards sequence converge and we end up with a finite summation of infinite terms.

Reinforcement Learning Set Up

Agent and environment

No longer have access to the transition model, and sometimes no access to the rewards model either.

So there’re the loss of two key components here; losing either makes the problem hard. Different applications might have different levels of lost access. For instance, often times in rigid-body robotics, we have at least the law of physics as a guiding principal and from that we get vague ideas of the transition.